The machine that mirrors us

Why our obsession with AI is really a conversation about humanity.

The year is 1859. Paris is bubbly with the buzz of salon, there is a lot of intellectual ferment and something new to be exposed next to paintings: Photography. A medium barely twenty years old, that is expanding across Europe and the United States.

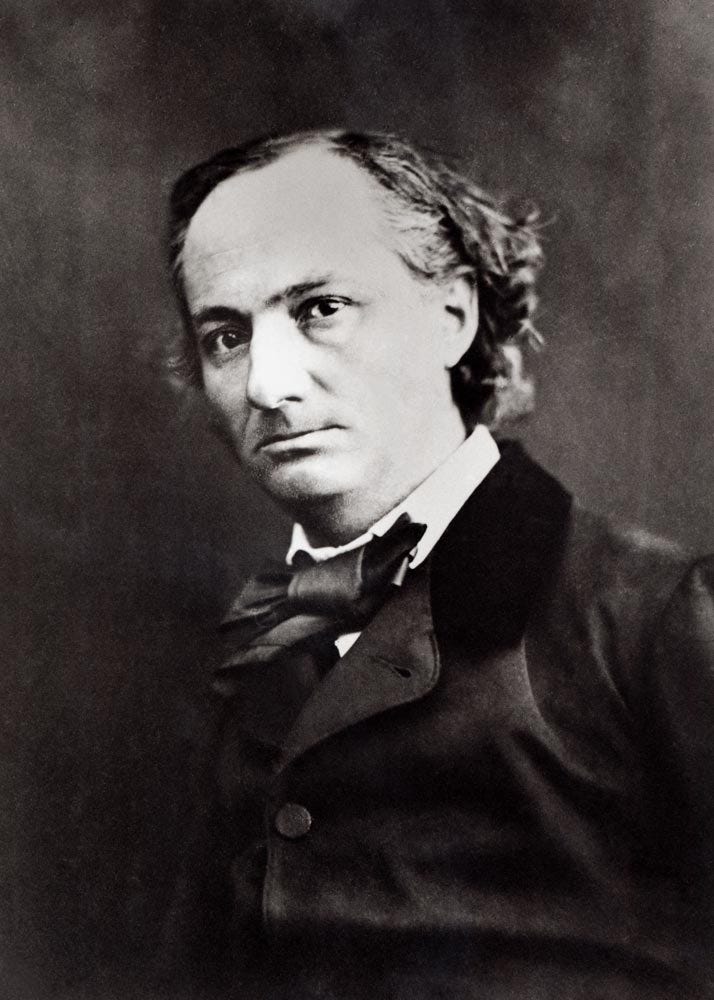

In response, Charles Baudelaire, poet, critic, and dandy extraordinaire, wrote some of the sharpest lines ever directed at a technology:

“A new industry has arisen which contributes not a little to confirming stupidity in its faith and to ruining what might have remained of the divine in the French genius… An industry that could give us a result identical to Nature would be the absolute of art… A vengeful God has granted the wishes of this multitude. Daguerre was his Messiah.”

Baudelaire’s words read like an early manifesto against the tyranny of mechanical reproduction, a lament that a machine could bypass the study, talent, and slow mastery of Art, real Art. But the story is more complex.

Baudelaire, one of the perfect dandies (or the everyman influencer?) used photography strategically. His portraits, many taken by Nadar, were carefully staged: the pose, the costume, the gaze. Through photography he created the persona we still associate with him today: the melancholic, ironic, cold observer. He critiqued photography as a soulless intrusion, yet he also used it to craft an icon, to objectify himself, to become unforgettable.

This contradiction, fear and fascination, critique and dependence, is not an isolated case. Artists across history have bristled at new media:

Delacroix worried photography would destroy painting, Rodin dismissed photographs publicly while relying on them privately, Pictorialists fought to “rescue” photography from its mechanical origins.

In each case, the tension wasn’t about the tool itself but about what the tool threatened in the artist’s identity.

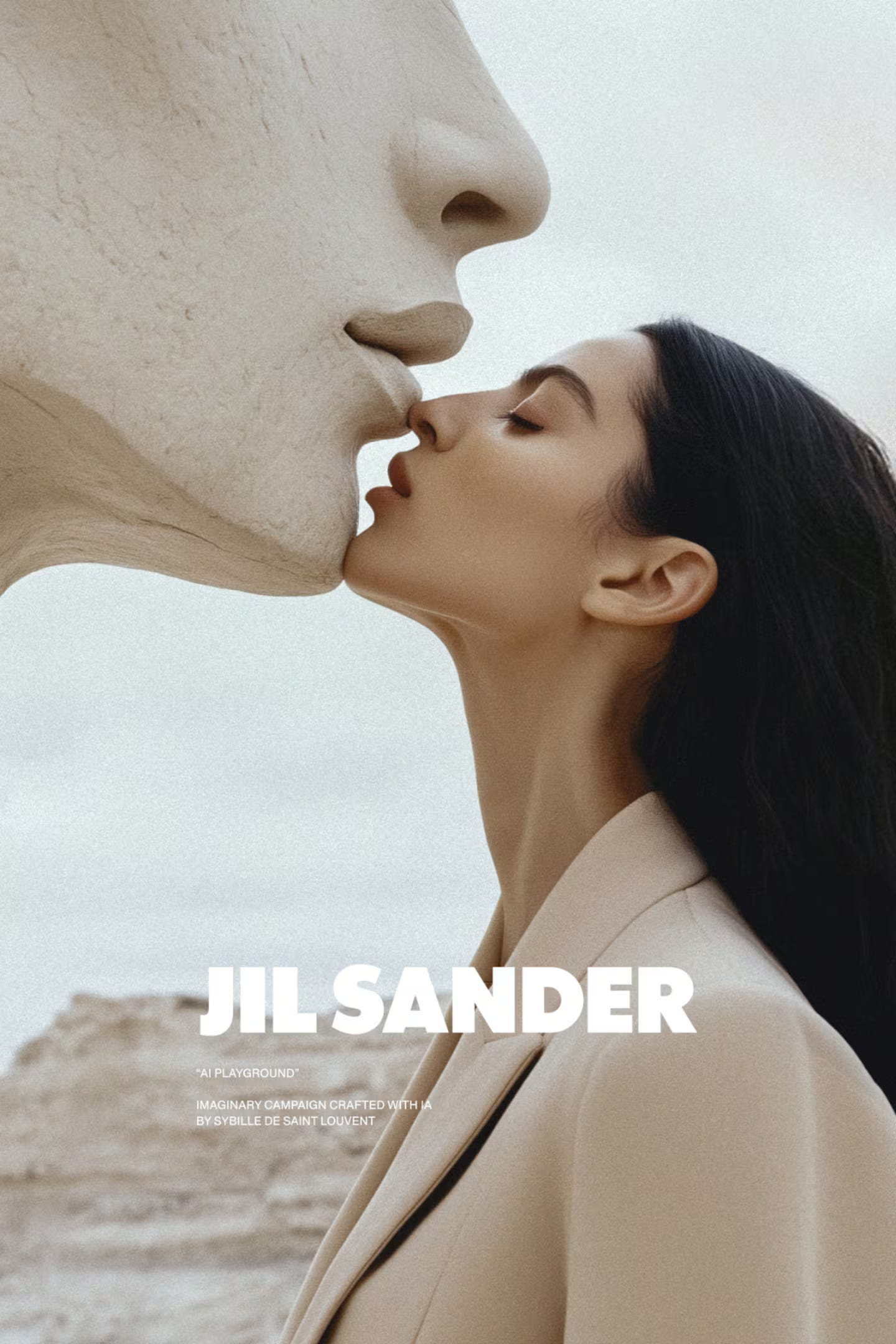

Let’s move fast forward to today, and the new medium is AI. Generative AI tools can produce images, drafts, videos, and music in seconds. The anxiety they provoke feels familiar, almost identical to the panic surrounding photography in the 19th century. Machines can now perform tasks that once required long apprenticeships and years of refinement.

But beyond the fear of being replaced lies something deeper: a shift in how we define effort, skill, and meaning. I’m thinking and debating a lot about this with different people that have different perspectives. I found this debate quite interesting, to analyse the different voices and where they place their attention. For a lot of them, it’s a new tool that will open a new horizon, for others it’s the end of creativity. For me, it’s a reason to deeply think about the consequences for future generations, privacy, image usage, inclusivity (but these points need an article apart from this one) and an anthropological study on human behaviour. And I think this is one of the main aspects people forget to take in consideration while this transformation is already happening. But let’s go by order.

The impact of AI is measurable and we already have some data. Creative professionals using AI report efficiency gains of 20–40%, with tasks like image editing or content drafting reduced by hours each week. Productivity has surged. I would be a hypocrite if I said I didn’t use some AI tools to improve my workflow for tedious tasks, to have more time to dedicate to tasks that are creatively fulfilling (like writing this article for example). However, even if productivity has increased there is some other interesting, and sad, pieces of data. Studies show that while AI supports many creative roles, others such as routine illustration, copywriting, design execution, etc face real risk. In the Future Unscripted: the impact of generative artificial intelligence on entertainment jobs, dated January 2024, researchers estimated that in the U.S. entertainment and creative sectors alone, 26,000–200,000 jobs may be displaced or fundamentally reshaped in the coming years.

Now think about the human perspective of these numbers. It’s easy to look at these numbers as just numbers, but try to visualise random faces of 200,000 different types of lives, disrupted. After the first 5 I got overwhelmed.

At the same time, entirely new professions are emerging. Demand for “AI-creative” roles, prompt engineers, AI workflow designers, curators of machine-generated content, has climbed dramatically, with some reports showing a 120% rise in these job titles since 2020. However, baring in mind these roles barely existed prior to the AI bubble, this statistic is not as impressive, nor are the roles numerous enough to cover the estimated lost wages. The amount of times I’ve applied for “photography jobs” that were actually lower paid AI image training roles are countless now.

Now consider the generational shift.

For younger creatives, growing up with AI means creation often feels effortless. What once required months of study, practice, and experimentation can now appear in seconds. While this acceleration is a gift, it also risks distorting the meaning of craft. The friction, the hours spent learning, failing, starting over, is part of what shapes artistic identity and taste. Without that struggle, creativity risks become a series of outputs rather than a lived practice.

From the perspective of the owner of a fashion business, now trained to receive a finished campaign in the least possible time, rather than wait a couple of days or weeks. Why choose something that requires time and creative input (and thus, higher cost), when you can have an okay result in less time and faster? It’s all about speed to market and costs, before the whole process starts again. With such an influx of content, more than can possibly be absorbed by the target consumer, cutting through the noise even with fully human-crafted campaigns becomes difficult. If you feel like nobody is watching, cutting corners to reduce cost can seem like a valid path. AI appears to improve productivity; vomiting out pictures that oftentimes are only created because something needs to be made. I know that I’m generalising here.

Moving to another important aspect I would like to consider is that AI reshapes not just how we work, but our psychology. Surveys show a rise in imposter syndrome among Gen Z creatives, who fear their skills are insufficient in a world where technical mastery can be outsourced to a machine. Some experience guilt for not having “worked hard enough,” others have anxiety about a future where craft itself seems optional. I feel you, anonymous Gen Z people, you are not alone.

We have seen this pattern before. Photography disrupted painters, then industrialisation replaced artisans, after that digital tools unsettled musicians, filmmakers, and writers. Humans have always met technological revolutions with fear, sometimes even terror, because each one reshapes how we understand our own value.

And yet, history also shows us the second half of the story.

Photography became an art, not because of its mechanical nature, but because artists reimagined what it could be. Industrialisation destroyed some craft, but generated others. Digital media sparked entire new cultures and opportunities. The terror of change rarely marks an ending: it marks a transition.

The work of Nick Knight perfectly mirrors Baudelaire: a titan of the fashion and avant guard photography world who is simultaneously an early adopter and vocal champion of the challenging AI, often justifying its use with the same arguments used to defend photography’s start.

It raises the question: Does using AI dilute his legacy (the technical skill of the “eye”) or is it the ultimate expression of their vision, curation, unconstrained by physical limitations?

Which leads me back to the deeper question. Baudelaire was not afraid of photography itself: he was afraid of mediocrity replacing the divine, and of a world where effort and genius could be flattened by a machine. Today, we are not afraid of AI per se, we are afraid of becoming interchangeable, of losing the link between effort and meaning, between craft and identity.

I think that every time we talk about AI, we are really talking about ourselves, and to ourselves.

Because technology forces us to ask what is uniquely human: taste, intention, judgment, context, vision, imagination and the emotional weight of lived experience.

Machines can replicate labor, but they cannot replicate longing, failure, or the interior life that makes art more than an artifact. They cannot replicate the time it takes to become someone.

In the end, the conversation about AI is not about machines, it is about what they reveal. Just as photography once exposed new truths through its “cruel” precision, AI exposes the anxieties and aspirations of our age. It pushes us to reconsider craft, identity, and the meaning of creation itself.

Technology challenges us, and in doing so, it clarifies who we are.

There so many other topics I would love to talk about regarding AI, for example how the manipulation of archival photographs reshapes our perception of the past, creating memories that never existed (or were never documented), how the biases embedded in our prompts quietly train the machine to echo our prejudices back to us, how these tools may one day alter not just what we create, but what we remember.

This essay only opens a door. The rest is a conversation, an invitation to look closer, question more, and shape the future with intention.

Giulia, it is so nice of you to give so much effort to the lives of those whose work will be disrupted by this future. I certainly agree that we are more often talking about ourselves... "AI destroys these industries," no, we destroy them because society is the way it is. Hope you're well~